Personal, National and Global Consequences ›

Prisoner Attitudes

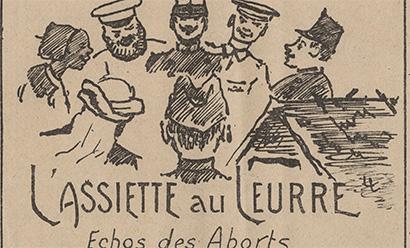

Print by Jean-Pierre Laurens. French. 1918. 2019.38.1.5. National WWI Museum and Memorial.

Prisoners were not convinced they should join the cause of the German-Ottoman alliance. Germany and the Ottoman Empire were counting on pan-Islamism to have a major influence on the prisoners’ attitudes, but the soldiers’ own views of religion and their ties to home regions proved stronger.

- Most Muslim prisoners did not find the Ottoman Empire’s calls for jihad valid. Many of the Muslim soldiers had a much different idea of Islam’s teaching about war and peace than the one presented at the camp. Few believed in the jihadist cause.

- The soldiers had strong ethnic and national ties. They did not see the success of a German-Ottoman alliance as a bigger cause than their own countries’ stakes in the global war.

Many prisoners had no desire to return to war, no matter the side or cause. Prisoners in the camp had recently left battlefields and were not eager to return to dangerous and deadly environments.

War Poems (chanted)

Sadak Berresid, composer and performer

May 30, 1916

Recorded in Wünsdorf-Zossen (Halbmondlager), German POW Camp

Playing time: 2:03 min/sec

Digital recording from roller

PK 257/2, Sound Archive, University of Berlin

Sadak Berresid, a French colonial soldier from Monastir in Tunisia, spoke and sang three “war poems” in Arabic to the gramophone as a prisoner of war in the Half Moon Camp on May 30, 1916. He tells his own story: how he was recruited by the French army in Tunisia during Ramadan 1914, was injured in Europe in a battle against the Germans, and was taken prisoner and interned in a prisoner-of-war camp. He shares his lack of medical treatment and his feeling of isolation in captivity. The poem ends with the words “Oh my God, help me!”

The spoken words and songs recorded by Sadak Berresid are part of the collection of the Prussian Phonographic Commission, which made 1,650 recordings in German prisoner-of-war camps between 1915 and 1918.

Sound recording courtesy of The Sound Archive, Humboldt University-Berlin.

Family and economic issues were also motivators. Many prisoners feared punishments for family in their home countries and a loss of their military pensions if they fought for the enemy.

Poster. 1917. France. Lithograph, printed by Devambez, Paris. 1920.1.344. National WWI Museum and Memorial.

Health concerns also played a role. By 1917, many of the prisoners from Africa and India fell ill. As a result, German leadership transferred them to Romania where they thought the climate would be more suitable for their health.

Stories from former prisoners who joined the cause also influenced prisoner attitudes towards Germany and the Ottoman empire. Volunteers who joined the Ottoman army were unhappy with their new military. The Ottomans used the volunteers at the Iraqi front, and most of the former prisoners felt badly treated by their Ottoman officers. The rough treatment led to frequent insubordination and desertion.

Leadership expected army volunteers to write enthusiastic letters to prisoners remaining at the Half Moon Camp, hoping this would inspire more prisoners to join the Ottoman army. Instead, the letter campaign backfired. The new members of the army wrote about abusive Ottoman officers, a lack of food and dangerous service.

Print, Photograph from periodical, "Der Grosse Krieg in Blidern," No.2. 1915. Germany. 2007.68.2. National WWI Museum and Memorial.