WWI and Jihad ›

Propaganda

The German Intelligence Office of the East put programs in place to influence prisoner behavior and shape opinions of the German Empire. These included newspapers, lectures, visits from officials, and outside media coverage. It also included resources dedicated to religious rituals and practices, as well as more leisure time and activities to boost prisoner morale.

Print, Photograph from periodical, "Der Grosse Krieg in Bildern," No 2. 1915. Germany. 2007.68.2. National WWI Museum and Memorial.

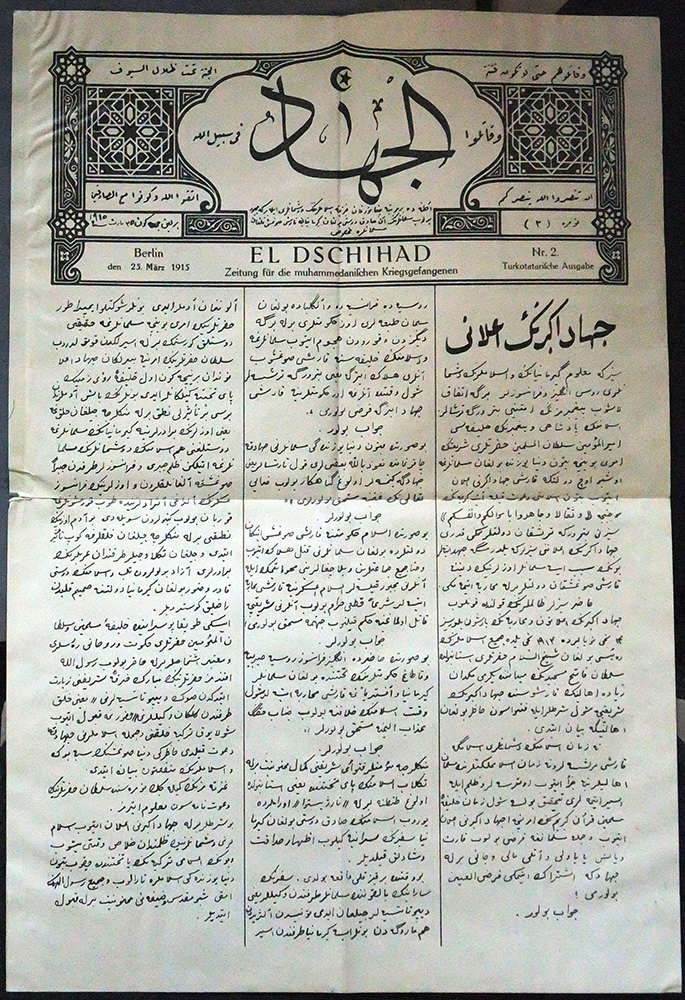

El Dschihad Turkotatar Edition No. 2. March 25, 1915. Germany. VIII Eu 27494. Museum of European Cultures of the Berlin State Museums - Prussian Cultural Heritage.

Newspapers

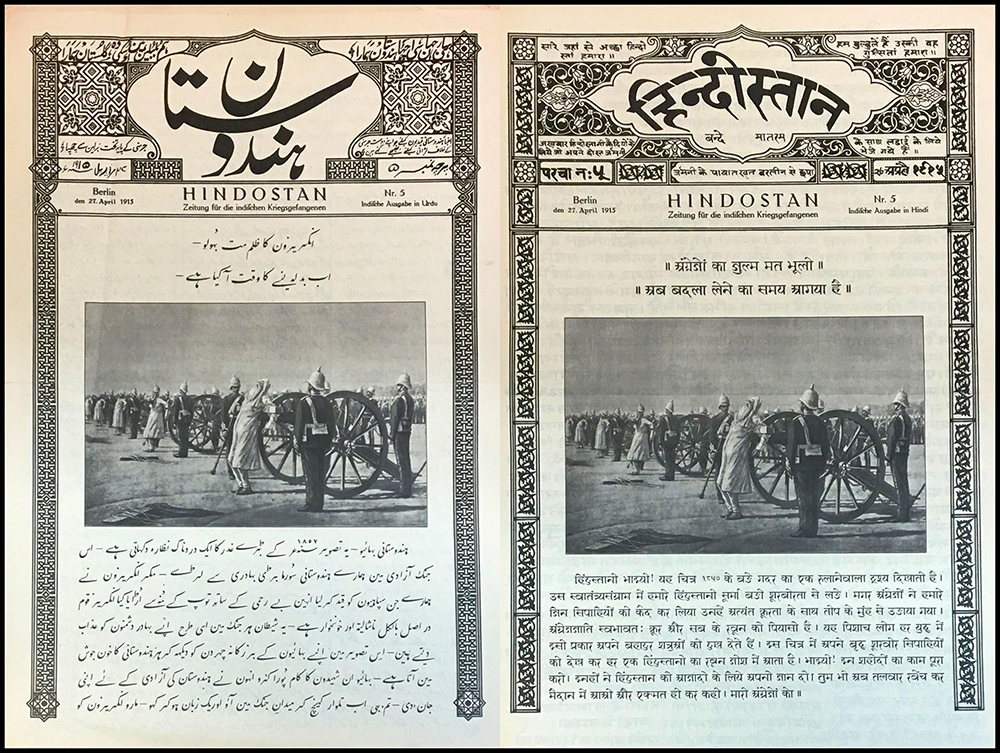

The German Intelligence Office for the East created foreign language newspapers for the prisoners of war. These papers aimed to portray the German Empire in a positive light. They featured articles reporting on the successes of the German military or cruelties of enemy empires against Muslims.

Hindi and Urdu editions of "Hindostan". April 27, 1915. Germany. D501.J53. Rare Books, Asian Reading Room, Library of Congress.

Educational lectures

Germany provided educational programs for the prisoners of war, often featuring outside speakers. Topics of lectures included agricultural and trade training or historical and political talks. Historical talks were intentional in their focus: German history, the history of Islamic peoples, or Germany’s relationship with Islamic countries.

“As a special goal, the military use of the camp inmates in the Orient should be striven for; in addition, the sympathy and interest of the people for Germany should be awakened to such an extent that after the end of the war they would become followers of Germany and return to their homeland…. [the means of propaganda will be] a) a religious influence b) instruction by holding meetings and lectures, giving lessons, group excursions in the vicinity of the camp, sightseeing of the Reich capital, etc., c) good treatment, food and clothing…”

—Max von Oppenheim, “Instructions for the Propaganda Camps”, December 1915

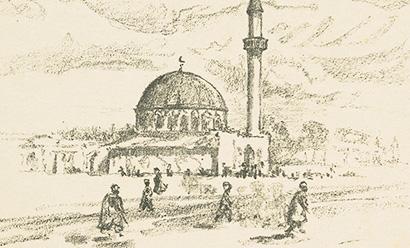

Print, Photograph. Circa 1914-17. Germany. VIII Eu 27543 b. Museum of European Cultures of the Berlin State Museums - Prussian Cultural Heritage.

Visits

Turkish, Tartar, and Arab officials often visited the Half Moon Camp. These visits tried to boost prisoner morale, and often focused on fostering pan-Islamic solidarity and jihad. Visits also provided rich material for reporters from German and Turkish newspapers.

“We set out early in the morning. The camp was quite a distance from the station where we got off; we boarded government cars there and had about 20 minutes to drive. From a distance we saw the scattered barracks… Passing through the scattered huts here and there, we came to a wide square. There they were, our Mohammedan brothers. There they stood on the prayer rugs spread out over this vast square that reminded us of the steppes. The distracted look in their astonished eyes gradually became firmer and surer; from their happy, expressive features, from their sunburnt lips, the last traces of that melancholy cry shone towards us: ‘Allahu ekber’ ‘God is great.’ These poor deluded ones gradually sensed the truth and, still wavering between doubt and certainty, smiled a happy smile, for it came from remorse and the hope of freedom.”

—Istanbul journalist Lemy Nihyd’s report on the festival held at the camp October 8, 1916 honoring an Ottoman foreign minister.

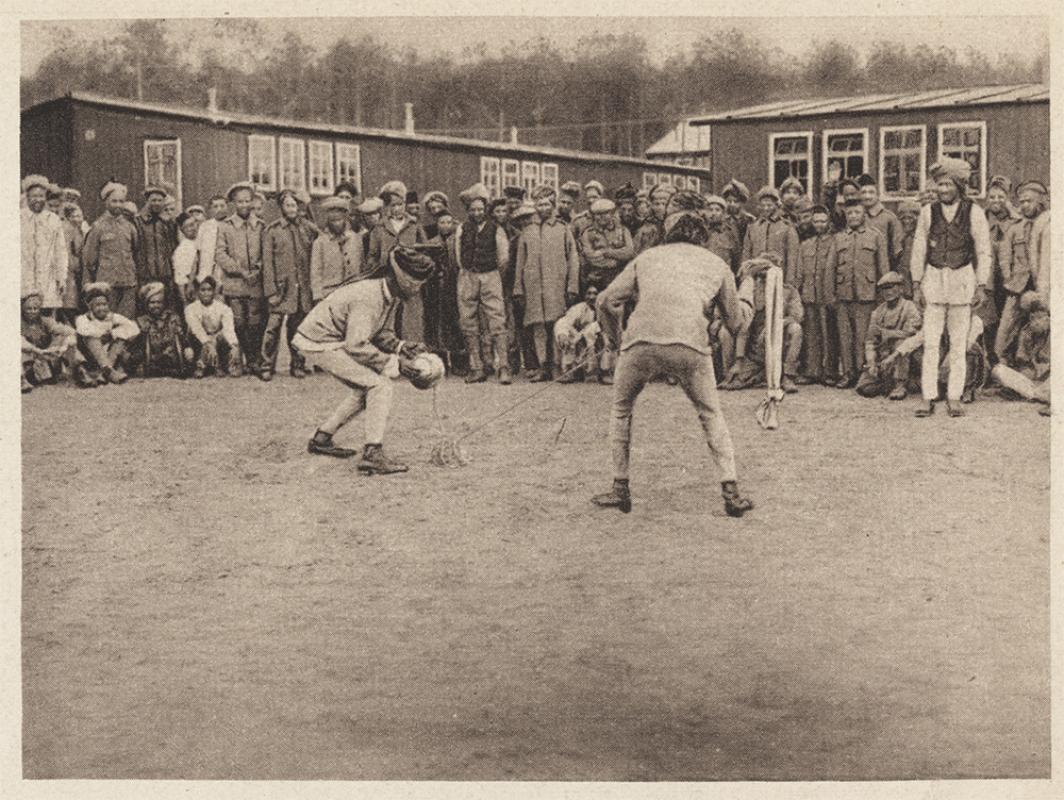

Print, Photograph from periodical, "Der Grosse Krieg in Bildern," No 17. 1916. Germany. 1986.51.3. National WWI Museum and Memorial.

Print, Photograph from periodical, "Der Grosse Krieg in Bildern," No 17. 1916. Germany. 1986.51.3. National WWI Museum and Memorial.

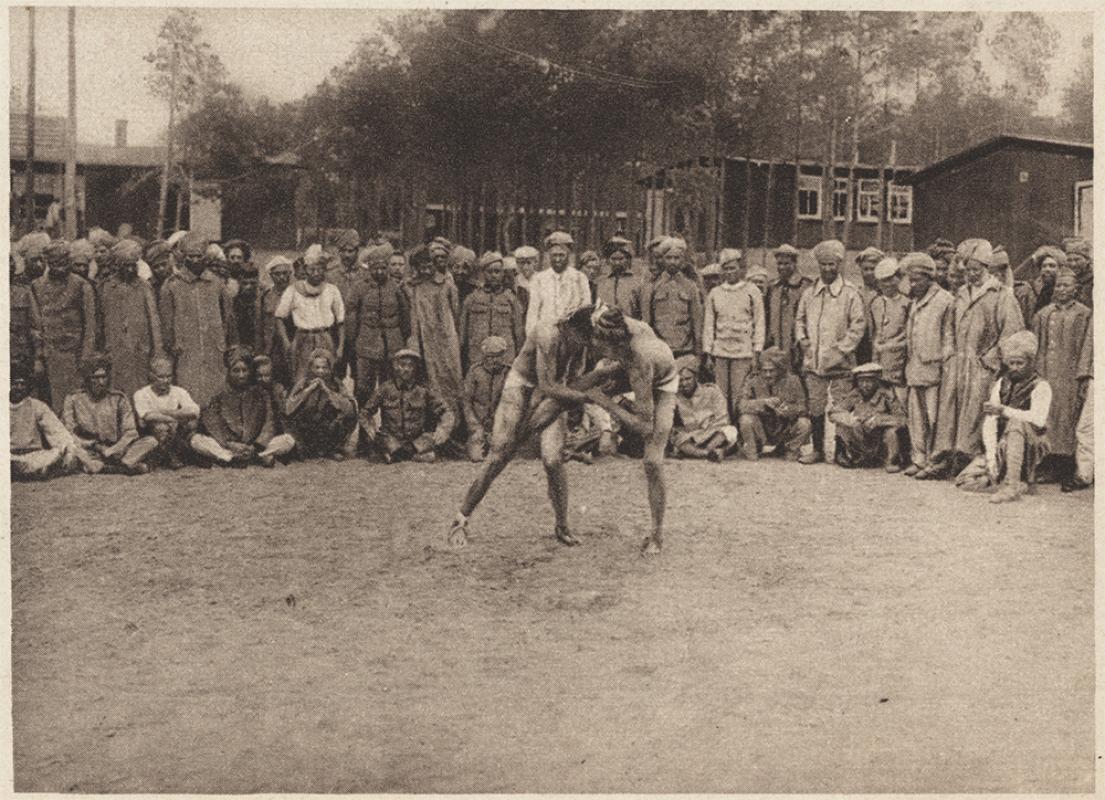

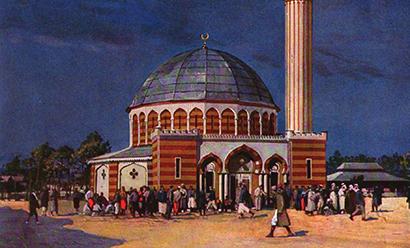

Print, Photograph from periodical, "Der Grosse Krieg in Bildern," No 9. 1915. Germany.

2007.68.9. National WWI Museum and Memorial.

Outside media

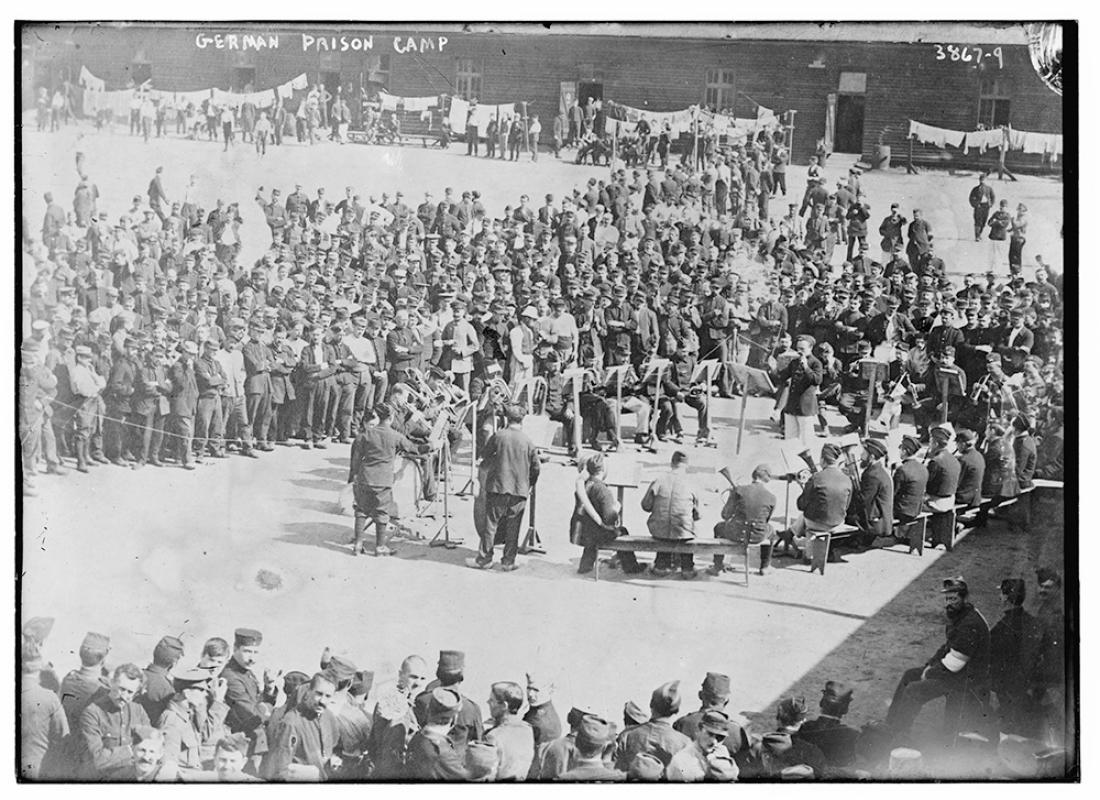

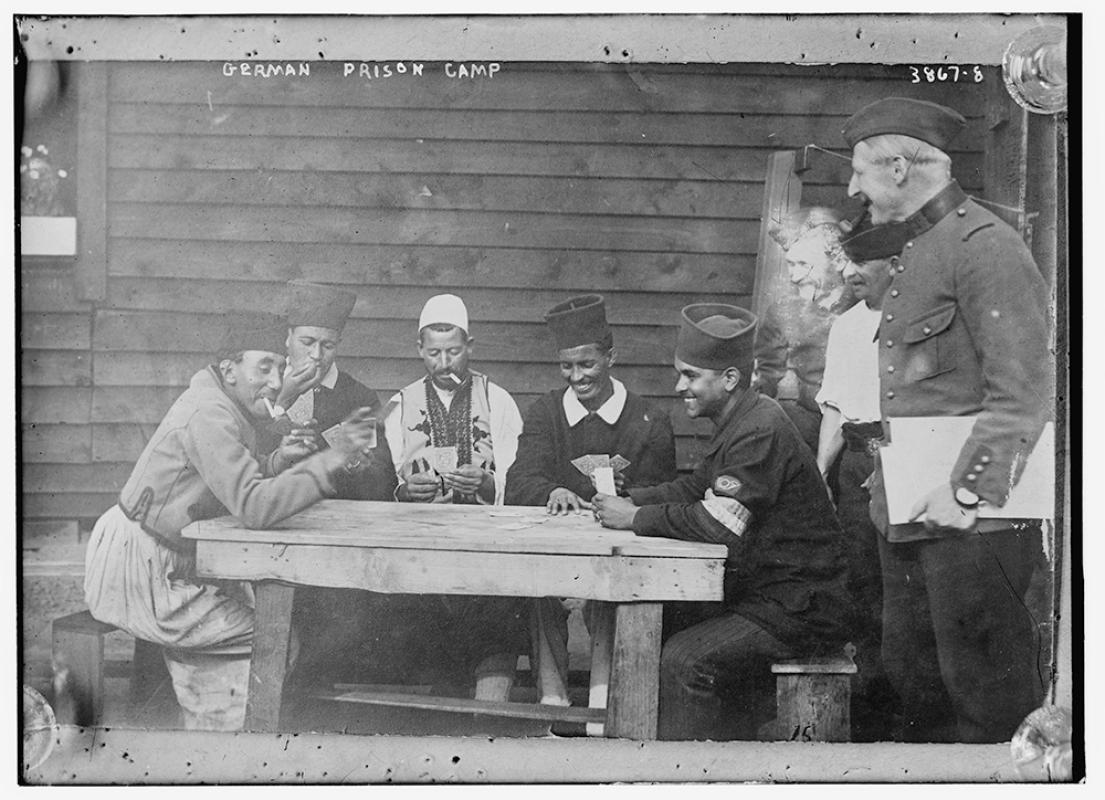

The camp advertised German treatment of prisoners at home and abroad. Camp leadership supplied the press with pictures and reports of Muslim prisoners. The German Intelligence Office of the East published magazines for readers outside of Germany. These materials were all meant to convince the world how well Germany thought of and treated Muslim prisoners.

Der Grosse Kreig in Blidern, a German periodical from which many photographs in this exhibition come, is an example of German external propaganda.

“We were very happy about (your treatment on the part of) the German government, namely that they in a benevolent way arranged for your prayer, fasting, studying the Koran, Friday prayer and a bath to keep you clean. May God bless them for that…. Your letters pass from hand to hand as soon as they arrive.”

—Letter from the father of Algerian POW Lymy Muyammar, September 6, 1915

Leisure Time

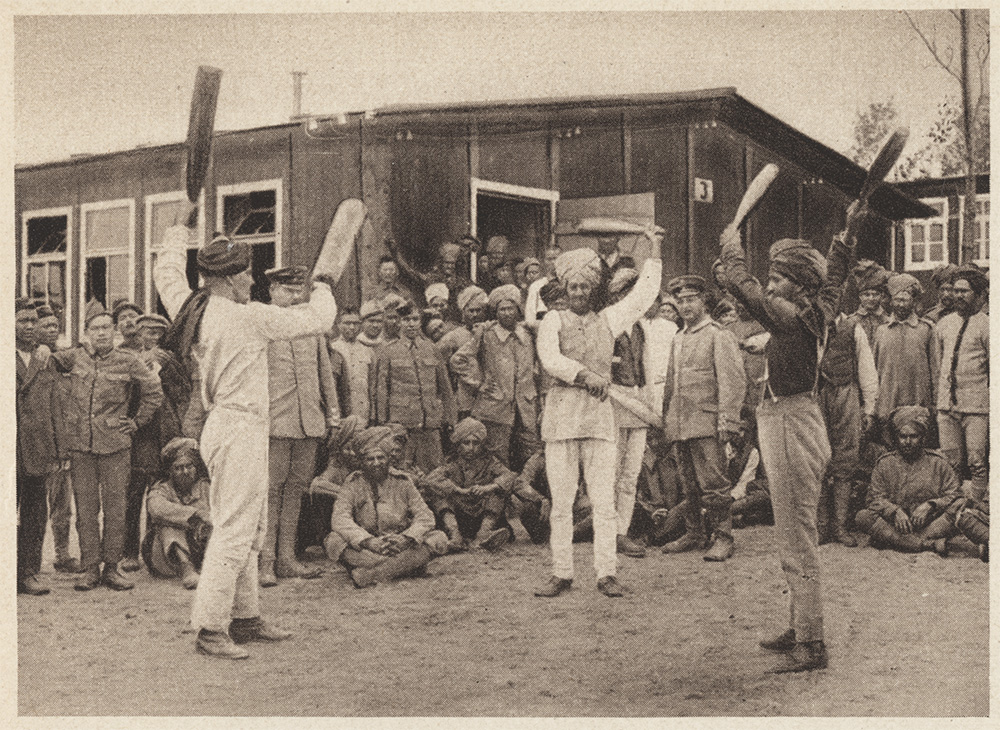

The propaganda included “extra” time for leisure. Prisoners of war were given more free time than other prisoners in German camps. This included entertainment like concerts, organized physical exercise and competitions, and time for cards and other leisure games. German officials often took photographs for propaganda publications showing the prisoners of war enjoying – perhaps staged – activities.

Food

German leadership ensured that prisoners of war were allowed to follow Muslim teachings and practices surrounding food. This influenced what kind of foods were served to prisoners, how prison butchers and cooks prepared food, and when prisoners would or would not eat certain foods. It included observations of periods of fasting as well as preparation of foods for breaking fasts, and meals for religious celebration.

Original caption translated from German reads:

April 28, 1915.

An Arab prisoner camp near Berlin,

In the vicinity of Berlin, in Zossen - Wünsdorf, a new Arab prisoner camp has now been set up, housing only Arabs and Spahis (light cavalry regiments of the French army). [...] The prisoners are certainly not to complain, their food is plentiful and as shown in the following list also rich.

For example [...] total consumption of food approx. 25,000 kg of mutton, 15,000 kg of pork*, 10,000 beef, 915,000 kg of potatoes, 10,000 kg of green beans, 40,000 kg of morels and turnips, 25,000 kg of white cabbage, 25,000 kg of cabbage and 5,000 kg of rice, barley and salt each.

This is just the consumption of a prison camp, how should we impress our enemies that we can do such a thing, even though we do not receive a supply now. At any rate, our enemies can not complain that they are starving, rather that they have to eat so much barbarously. [...]

Note: Pork was probably for non-Muslim Russian POWs.

Print, Photograph. April 28, 1915. Germany. Bild 146-1995-051-33. German Federal Archives.